The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

|

|

Alexandre Cabanel's Portraits of the American 'Aristocracy' of the Early Gilded Age |

|||||

|

As vast fortunes were being accumulated in the wake of the Civil War, social and cultural roles were being forged to match that wealth. Art played an important part in creating the appropriate image of money and power and, as the critic Edward Strahan (a.k.a. Earl Shinn) recorded in 1879, wealthy Americans amassed collections of contemporary European art, mainly French and academic.1 They were also eager to have their portraits painted, preferably by artists of note whose reputation would lend an air of cultural sophistication to their pictorial images. For such portraits, too, many Americans turned to French painters. While men's portraits tended to be rather sober and direct, women's portraits were more subtle. What was the public image prosperous American women were trying to project in their portraits? Kathleen McCarthy wrote that upper-class women in the Gilded Age forged public roles through philanthropic endeavors.2 However, when it came to their portraits, most wealthy women chose to be represented in their prominent roles as society figures; roles that were most obviously expressed by their demeanor, dress and accessories. | |||||

| One French artist, Alexandre Cabanel (1823-1889), was especially successful in capturing the public image desired by these wealthy women. Today, Cabanel is known almost exclusively for his Birth of Venus, exhibited in the Paris Salon of 1863. His other works—history and genre paintings as well as portraits—have been largely ignored by scholars. However, by the 1870s, many American collectors, such as William Astor, William T. Walters, William H. Vanderbilt, and Jay Gould, to name a few, had purchased Cabanel's historical paintings, and others like silver mine millionaire John W. Mackay, and the inventor of the reaper, Cyrus Hall McCormick,3 had commissioned portraits of themselves and of their spouses from Cabanel.4 Cabanel was well known as a portraitist and in the 1870s and 1880s he was the painter of choice for Gilded Age Americans, particularly women, who desired an aristocratic image to match their wealth. In 1879 an American critic estimated that, aside from Ernest Meissonier, Cabanel was the best-known French artist in the United States.5 | ||||||

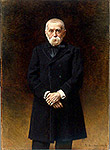

| Cabanel's reputation in the United States was preceded by his success in Paris where, by the 1860s, he was already a favorite portraitist of European aristocracy, especially women. An established and decorated history painter, Cabanel did not need to paint portraits for money, but he seems to have enjoyed painting portraits and chose to exhibit them frequently in the Paris Salons. His portrait of the Countess Clermont-Tonnerre, exhibited in the Salon of 1863, and the portraits of the Viscountess of Ganay (an American) and Emperor Napoleon III (fig. 1), both exhibited in the Salon of 1865, attracted critical attention in France as well as in the United States for their distinctive contemporary style.6 | ||||||

| Cabanel's portrait of Napoleon III won the artist a Medal of Honor at the Salon of 18657 and was praised on both sides of the Atlantic for its simplicity and sophistication. Roger Riordan, writing for the Art Amateur, claimed that it was Cabanel's best portrait.8 French writer Henry de Chennevières praised Cabanel's modest representation of the emperor as a bold, modern, and original conception.9 Rather than portray the Emperor in his imperial finery, Cabanel depicted him wearing a simple black evening suit; the imperial robes lay on a chair behind him. The combination of modesty with an aristocratic air impressed the Americans as well as the French and may well have been an impetus for wealthy Americans to choose Cabanel for their likenesses. The artist's reputation, no doubt, was an even greater draw. Who would be a better choice for the American nouveaux-riches, those aspiring "aristocrats," than the man who had painted an emperor? | ||||||

|

Cabanel's reputation was enhanced by the many portraits he painted of female European aristocrats. While his early portraits of French women tended to be heavily accessorized, in the manner of the portraits of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, with whom he was frequently identified,10 Cabanel's portrait of the Duchess of Vallombrosa (fig. 2), exhibited in the Salon of 1870, is more in line with his later portraits of American women, who preferred simple backdrops and few accessories. The portrait of the Duchess, one of the few of his female portraits to have been reproduced in contemporary publications, received positive reviews in periodicals such as L'Artiste and Le Temps. A critic for L'Artiste called the portrait a "masterpiece," in which the soul shone through the eyes.11 Herton, writing in Le Temps, admired the "aristocratic elegance" of the work and noted that the portrait had a "boneless" quality, a remark that calls to mind similar comments about Ingres' figures as well as Cabanel's own Birth of Venus.12 But unlike Ingres, Cabanel did not overtly manipulate the figure for aesthetic reasons, though he did subtly elongate limbs and necks to create more flowing lines. | |||||

|

Cabanel's earliest portrait of an American may be that of Mrs. John Jacob Ridgway of Philadelphia dated 1861 (location unknown).13 Portraits of sitters that I have identified as American that he exhibited at the Paris Salon were those of the Viscountess of Ganay, John Jacob Ridgway's daughter, Salon of 1865; John W. Mackay, Salon of 1879; Eva (Eveline Julia) Mackay, John Mackay's step-daughter, Salon of 1881; Eveline Hungerford, John Mackay's mother-in-law, Salon of 1883; a Miss A. Ogden of Chicago, Salon of 1884; and Mary Victoria Leiter, Salon of 1888 (fig. 3). In the United States, his portraits could be seen in exhibitions at the National Academy of Design (1876, 1898) and at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1875, 1876, 1887). | |||||

| Praised as a portraitist of women, Cabanel expressed that he was particularly adept at painting portraits of American women. In an interview translated in an American journal, he said, "I have painted the portraits of a great many Americans, the delicacy and grace and refined type of American beauty being peculiarly congenial to my pencil."14 C. Stuart Johnson, writing in New York's Munsey's Magazine, stated that Cabanel was the best portrait painter of his time.15 In Edith Wharton's famous novel set in the Gilded Age, The Age of Innocence, Cabanel's name was mentioned three times; twice in the context of his famous portraits.16 A French critic also noted Cabanel's popularity with Americans: "The effect produced among the American colony in Paris may be readily imagined, and at the present time every American of any pretensions rushes to Cabanel's studio."17 Pretensions, in this context, probably refer to aristocratic pretensions, or American social and cultural aspirations to rival the Europeans. | ||||||

| Americans who desired a portrait by the master had to travel to Paris to sit for him—Cabanel never came to the United States. This would not have been problematic for most, since overseas trips were de rigueur, and probably enhanced the value of the portrait back home.18 Socialites from the United States often went abroad to mingle with the European social elite and true aristocracy, and some wealthy American families, like the Mackays, kept mansions in Paris and entertained regularly.19 | ||||||

| While many American women sat for Cabanel during their overseas trips, men often sat for Léon Bonnat (1833-1922), whose renown as a portraitist nearly equaled that of Cabanel. Bonnat's portraits were usually three-quarter length, somber, and dignified. Their format, dark palette, and brushwork were inspired by the works of Spanish artists such as Velázquez and Ribera, and led many to consider him a "manly" painter.20 Bonnat was, thus, a natural choice for male sitters, such as William T. Walters (fig. 4). He became popular with wealthy Americans in the late 1870s, following the enthusiastic reception of his portrait of the celebrated French actress Madame Pasca at the Salon of 1875.21 His reputation as a portraitist of men was solidified the following year by the success of his portrait of Adolphe Thiers, the first of several French presidents he painted. Cabanel's portraits shared a similar format, often three-quarter length with the sitter looking directly at the viewer, but they were lighter in palette, more carefully modeled and smoothly finished; features that were especially suitable for women's portraits.22 | ||||||

| Patrons did not often approach artists directly to commission paintings. Instead, dealers such as the Americans George A. Lucas and Samuel P. Avery usually acted as liaisons between American clients and Cabanel, Bonnat, and other European artists. Lucas was originally from Baltimore and worked in Paris, and Avery was based in New York but made frequent trips to Paris. Both men kept diaries in which they recorded their business arrangements.23 Lucas negotiated with Cabanel and Bonnat on behalf of Baltimoreans Robert Garrett and his wife Mary Frick Garrett, later Mrs. Henry Barton Jacobs (fig. 5), to have their portraits painted in Paris, and accompanied them to the artists' studios.24 Robert sat for Bonnat, and Mary sat for Cabanel; her portrait was begun in early June of 1885 and completed in late September of 1885. There are no references to portrait arrangements with Cabanel in Avery's diary, although he mentioned seeing a portrait of Arabella Worsham, later Mrs. Collis Potter Huntington (fig. 6) on September 5, 1882.25 Although he did not explicitly state that she made arrangements through him, this was likely the case. | ||||||

| The diaries contain little information about the prices Cabanel charged for his portraits, except for the amount the Garretts paid: 20,000 francs, (about $4,000 at the time), to Cabanel and 20,000 francs to Bonnat.26 It may be assumed that Cabanel charged similar prices for his other portraits.27 The diaries do divulge amounts for other artists: in May 1879, Bonnat asked for 25,000 francs to paint a full-length portrait, or 15,000 francs for a three-quarter-length portrait, of one General Brown; in 1880, Carolus-Duran (Emile-Auguste Carolus-Duran) (1838-1917) asked Lucas for 15,000 francs for a full-length portrait and 12,000 francs for a three-quarter length portrait of a woman.28 By the 1890s, Carolus-Duran charged $4,000 to $8,000 for a portrait.29 | ||||||

| Among Cabanel's numerous female American sitters were Eva Mackay and Mary Victoria Leiter, both of whom, shortly after their portraits were painted, married European aristocrats, thus realizing for their mothers the dream of many of the nouveaux-riches of the Gilded Age with aristocratic pretensions. It is interesting to speculate to what extent their portrayal by Cabanel played a role in the arrangement of their successful marriages. Certainly the portraits were meant to impress, and both of these women's portraits were exhibited (and advertised) at the Paris Salon for all to see. Mackay's portrait was also exhibited in the Exposition Nationale of 1883 in Paris. Although identified in the Salon catalogs with only the sitters' initials, Salon-goers of a certain class would recognize them.30 Within a few years after her portrait was completed, Eva Mackay married an impecunious Italian aristocrat, Fernando di Colonna, Prince of Galatro in 1885. Her portrait was said to be so fine that even one of Cabanel's detractors, French critic Edmond About, had to sing its praises.31 The current location of the portrait is unknown. | ||||||

| Mary Leiter was the daughter of Levi Leiter, a dry goods millionaire who co-founded Leiter & Field, now known as Marshall Field's department store, and also served briefly as president of the fledgling Art Institute of Chicago. Her portrait was painted when she was a debutante and aspiring to be socially prominent. Leiter and her mother sat for Cabanel on a trip to Paris in 1887, and Mary's portrait was exhibited at the Salon the following year, where it attracted favorable attention.32 She was known for her beauty and sophisticated demeanor, two of her most praised social assets, which are clearly reflected in her portrait.33 Shortly after her successful society debut in Washington D.C.— closely followed by the exhibition of her portrait—Leiter's mother was anxious for her to marry, and after several disappointing trips to Europe, the Leiters traveled to England where Mary won the heart of George Nathaniel Curzon, later Marquess of Kedleston, in 1890.34 They married in 1895, and Mary Curzon became the vicereine of India from 1899 to 1905, the highest political position held by an American woman of the time.35 Today her portrait hangs in Kedleston Hall, in Derbyshire, England. | ||||||

|

Other portraits of American socialites painted by Cabanel include those of Catharine Lorillard Wolfe (fig. 7), Olivia Peyton Murray Cutting (fig. 8), Mary Frick Jacobs (fig. 5), and Arabella Huntington (fig. 6). These women sat for Cabanel when they were already married, except Wolfe, and had achieved stature in their philanthropic and social roles. Wolfe, the first female subscriber to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, bequeathed to it her art collection—including her portrait—along with an endowment of $200,000 for its upkeep.36 She also left a large sum of money to Grace Church on Broadway and Twelfth Street in New York City, which owns a loosely-painted replica of her Cabanel portrait from the hand of the prolific American portraitist Daniel Huntington.37 Cutting was a philanthropist and the wife of railroad baron, William Bayard Cutting.38 Jacobs, a childless philanthropist, was one of the leading hostesses in Baltimore, presiding over many lavish balls held in her grand townhouse.39 Married to Robert Garrett, president of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, at the time her portrait was painted, Jacobs bequeathed her art collection, including the portrait, to the Baltimore Museum of Art.40 At the time Arabella Huntington had her portrait painted, she was probably widowed from John Worsham, who had been the owner of a gambling parlor.41 She later married New York railroad magnate Collis Potter Huntington, and then Collis' nephew, Henry E. Huntington. Her son Archer Huntington bequeathed her portrait to the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in 1940. |

||||||

|

Why would these prominent women all choose Cabanel to paint their portraits? Cabanel had the ability to lend his sitters an air of gentility and urbanity, and to give them an aristocratic allure. The terms "elegance," "grace," and "refinement" appear frequently in comments on Cabanel's portraits.42 An obituary noted that "no modern artist delineated ladies with more simple grace or elegant reserve than Cabanel."43 But Cabanel's contemporaries saw even more in his portraits than elegance and grace. Perhaps C.H. Stranahan best summarized the contemporary appeal of these portraits in her History of French Painting, published in 1888, just prior to Cabanel's death. She wrote of Cabanel:

His careful combination of expression, gesture, fashion and finish imparted to each woman not just a pleasant appearance, but an enchanting presence, as exemplified in the portraits of Wolfe, Cutting, Jacobs, Huntington, and Lady Curzon. |

||||||

|

Cabanel's three-quarter length portrait of Catharine Lorillard Wolfe, painted when the sitter was in her mid-forties, exemplifies the attention the artist paid to his sitters' posture and especially to their hands which, he found, were too often neglected in portraiture.45 Wolfe had a reputation as a pious woman, a great philanthropist, and a gracious hostess,46 and in her portrait she appears ready to welcome guests. What struck critics most were Wolfe's lady-like comportment, and her well-placed, beautifully rendered hands. One American critic admired the "cultured gesture" of the hands,47 while another called the portrait "an exquisite specimen of Cabanel's skill as a painter of dames du monde," and added that Wolfe's "fine personality" permeated the picture.48 A third commented:

This description of Cabanel's portrait of Wolfe seems accurate when compared with an engraving of Wolfe, (fig. 9), possibly from a photograph, in which she wears a stern expression, a prim dress, and long gloves that cover limp hands. Cabanel transformed Wolfe's appearance from unremarkable to striking. He paid close attention to the costume as well as to the hands, and carefully painted Wolfe's gorgeous white satin evening dress with its plunging neckline trimmed with Russian sable and its lace-trimmed cuffs, an example of the latest in contemporary fashions from Paris, possibly by Worth, the most sought-after fashion designer of the time.50 Cabanel was especially successful in rendering the shimmer of satin and the softness of fur, and made prominent a chic detail in her gown: the colorful striped fabric gathered in her bustle swag. It was expected of the upper class gentlewoman to make at least one annual pilgrimage to Paris to refresh her wardrobe,51 and Wolfe made frequent trips to Europe.52 |

|||||

| Olivia Cutting sat for Cabanel in 1887, when she was in her early thirties; her husband sat for Bonnat.53 She wears an off-the-shoulder pale rose satin gown adorned with nothing more than a single pearl at the center of her décolletage and a single-strand pearl necklace around her slim neck. In her hands she displays a partially opened fan, a common accessory of the fashionable society woman. Like Wolfe, Cutting is portrayed in a stylish evening gown, the cut of which begs the question of propriety. The seductiveness of her appearance is neutralized, however, by the viewer's knowledge of her wealth. Wealthy women could wear low-cut evening gowns and maintain propriety while their poorer counterparts could not. Furthermore, the potentially risqué appearance of her dress is offset by Cabanel's representation of the sitter in a dignified and self-assured pose, a necessity for a well-bred woman,54 and by the airy, even ethereal quality he gave to many of his portraits of women. Émile Zola, one of Cabanel's detractors, made the somewhat sarcastic and somewhat truthful observation in 1868 that Cabanel "transforms the body into a dream."55 While Zola may have considered that quality uncomplimentary, Countess Laincel-Vento, author of Les Peintres de la femme, extolled Cutting's portrait for her aristocratic appearance and her "divinely elegant shoulders" as well as her "dreamy youth."56 | ||||||

|

Mary Frick Jacobs, in her portrait dated 1885, gently grasps a lorgnette, monogrammed with her initials, in her left hand, as if she has stopped briefly at Cabanel's studio for a quick sitting before dashing off to the opera. The inclusion of this prop—Stranahan's "judicious use of accessories"—hints at her cultured status, since the opera was considered an elite leisure activity, and every society member had, or coveted, an opera box.57 She is wearing a pale ivory gown similar in style to Cutting's, which is set off against the same dark-colored tapestry background Cabanel used for both Cutting's and Wolfe's portraits. Her soft, rounded shoulders and long neck are devoid of jewelry. A ring and a bracelet are the only accessories she wears. Jacobs wistfully gazes out at the viewer with her head slightly tilted to one side, while on her lips she wears a slight, wan smile, reminding us of Stranahan's comment regarding Cabanel's ability to lend to his sitters' faces "a tinge of interesting sadness." Her wistful expression, mannered hand gesture, and a lorgnette are also found in a photograph of Jacobs.58 |

||||||

| In her almost life-size, full-length portrait, dated 1882, art collector and philanthropist Arabella Huntington, known as Belle, wears a rich red velvet gown, with black lace trim around the sleeves and décolletage. Her accessories include small, dark blue earrings, a prominently placed, shiny gold wedding band, a bright red corsage, and an open fan made of red feathers, which she holds in her right hand. Leaning on a swath of heavy fabric draped over a gilt-wood carved open armchair, she exudes poise and confidence. Barely noticeable is her pince-nez, an allusion to her notoriously bad eyesight. Cabanel felt this portrait was one of his best and regretted that Huntington carried the portrait off without allowing him to exhibit it in Paris, although he exhibited it in his studio.59 | ||||||

| In all these portraits, Cabanel captured the public image that the sitters of the Gilded Age desired to present, and that suited their social needs. The public for these portraits were members of the same social class who would have seen them in each other's homes, and understood the importance, and cost, of owning such a work. A portrait by Cabanel was "a consecration of elegance."60 In their portraits, the sitters wear the most fashionable evening dresses, which would have been worn only to social events such as a ball or the opera; the social venues over which they dominated. As the women were not depicted wearing much jewelry—a display of jewelry would have been considered in poor taste— these gowns were the main indicators of their wealth. The modish gown, coupled with a dignified bearing and reserved facial expression, formed the appropriate image. | ||||||

| While little specific information is available about the placement of these portraits in their owners' homes, it appears that many were hung in the drawing room where guests were received. Cabanel's portraits of Eva Mackay's parents, John and Marie Louise, were hung in "places of honor" on either side of the doorway of the drawing room at the Mackay's new London mansion at 6 Carlton House Terrace during its inaugural reception on June 25, 1891, and Marie's son noted that the host and hostess received many compliments on their portraits.61 Wolfe's portrait hung over the mantel in her library until a year before her death, when it was moved to her dining room, where she had a recess constructed to accommodate the portrait.62 According to a contemporary visitor, she accorded another work by Cabanel to a prime spot in her drawing room, the Shulamite (Salon of 1876), which Wolfe had commissioned.63 Because Marie Mackay considered the prime placement of her portrait in the drawing room vain,64 I interpret the placement of Wolfe's portrait in her library as an exhibition of modesty. It did, however, hang prominently in her collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art after her death.65 | ||||||

| Leiter's portrait occupied a significant place in her wedding reception in 1895. Leiter, dressed in a Worth gown, and George Curzon, held their reception in the Leiter's Washington D.C. mansion. For their receiving line, the couple stood before the grand fireplace in the Leiter's drawing room beneath Cabanel's portrait of her, the frame of which was adorned with forget-me-nots for the occasion.66 Perhaps the prominent placement of the portrait was related to the role it had played in their courtship. It may also have suggested the role the portrait was to play in keeping Leiter's memory alive in her parents' home. The forget-me-nots were appropriate, given that the couple, soon after the wedding, sailed for England, never to return to the United States. | ||||||

| While most contemporary critics praised the grace and elegance of Cabanel's portraits, there were some who complained of his lack of interest in his sitters' individual traits and character. One American critic complained that Cabanel flattered his sitters as he idealized the figures in his mythological paintings and that he concentrated on lovely representations rather than character.67 French critic Charles Blanc referred to Cabanel's portrait strategy as showing his sitters' "Sunday faces."68 What these critics failed to see, or refused to concede, is that Cabanel was bound by his sitters' social code. These women were expected to hold themselves with dignity and aloofness as they were to be seen and admired. Any display of eccentricity in a formal portrait would have been alarming to their exclusive social set. Cabanel was expected to deliver a public image for his sitters of cool detachment, with the aura of wealth, dignity, and reserve expected of a well-heeled, upper-class American society woman in the 1870s and 1880s. | ||||||

| Cabanel did depict personality, but in subtle ways, through posture and expression. Looking out of the picture to meet the gaze of the viewer, the portraits of Wolfe and Huntington convey an impression of strong, self-possessed women. Due to their marital status—the former never-married, the latter thrice-married and the father of her child never definitively established69—these two women did not quite fit the mold of the respectable married woman, yet their wealth, social status, and philanthropic endeavors, had helped them overcome societal prejudices. The portraits of Cutting, Jacobs, and Leiter show the softer side of some of the Gilded Age society women, displaying that "interesting tinge of sadness" Stranahan mentioned. | ||||||

| After Cabanel's death in January, 1889, many patrons began to prefer the services of the younger portraitists who painted in a new, loose, bravado style—artists like Carolus-Duran, Giovanni Boldini, and John Singer Sargent; yet, Cabanel's tighter, more polished treatment of the sitters lived on in the portraits painted by his former student, Théobald Chartran, who was popular in the later Gilded Age.70 Had Cabanel himself lived on, I suspect that he would have successfully continued painting portraits of Americans well into the 1890s, as did Bonnat. | ||||||

| Today, Cabanel's portraits are rarely seen, and the locations of many of them are unknown. The ones that are owned by museums are for the most part in storage, reflecting the lack of interest in early Gilded Age portraits, especially those painted by French rather than American painters. Cabanel's portraits have not been included in studies of American portraiture and their neglect has prevented a full understanding of the development of this genre during the early Gilded Age.71 It also has deprived historians of a group of "documents" that provide important insights into the culture of this colorful period in U.S. history. | ||||||

| Edward Strahan expressed the opinion that Cabanel's portrait of Wolfe reflected "the national character of a period."72 Indeed, Wolfe's portrait and Cabanel's other portraits of wealthy American women show how these women wanted others to view them—beautiful, cool, elegant, and cultured. Cabanel's controlled and smoothly finished style, his cool palette, and his preference for traditional poses lent to his portraits the aristocratic allure that the nouveaux-riches of the early Gilded Age not only desired but needed to secure their social position as members of the new ruling class in America. For these women a portrait by Cabanel, portraitist of the Emperor, acted not only as a "consecration of elegance," but also, by its presence at the Paris Salon, as an introduction into the European beau monde, as the portraits of Mary Leiter and Eva Mackay indicate. By lending his American models the elegance and glamour of his portraits of the French nobility, Cabanel sanctioned their aristocratic pretensions. | ||||||

|

I would like to extend a warm thanks to those who have read and commented upon various drafts of this article: the managing editor, Dr. Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, my anonymous reviewer, copy editor Robert Alvin Adler, Dr. Patricia Mainardi, Dr. Sally Webster, Dr. Jane Roos, Elizabeth Watson, Heather Lemonedes, Paul Tutwiler and Miriam Beames. Audience members asked thought-provoking questions at symposia held at the Dahesh Museum of Art, New York, and at the Cleveland Museum of Art at which I presented earlier versions of this paper. I am also grateful to Dr. William Gerdts, who shared his Cabanel file with me several years ago which got me started on this project. Those who allowed me to view Cabanel's portraits in storage deserve a special thanks: Eileen K. Morales, Museum of the City of New York; Patrice Mattia, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Sona Johnston, Baltimore Museum of Art; and Stephen Lockwood, California Palace of the Legion of Honor. All translations, unless otherwise noted, are the author's. 1. Strahan 1879. A list of the works in each featured collection follows the end of each chapter. See for example, vol. 1, pp. 52, 64, 80, 94, 106, 118, and 134. 2. McCarthy 1991, p. xii. 3. Dates, where known, are as follows, in the order of mention: William Astor (1848-1919), William T. Walters (1820-1894), William H. Vanderbilt (1821-1885), Jay Gould (1836-1892), John W. Mackay (1831-1902), Cyrus Hall McCormick (1809-1884), Ernest Meissonier (1815-1891), Emperor Napoleon III (1808-1873), Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), Eva (Eveline Julia) Mackay (1861-1919), Mary Victoria Leiter (1870-1906), Léon Bonnat (1833-1922), Mme.Pasca (1835-1914), Adolphe Thiers (1796-1877), George A. Lucas (1824-1909), Samuel P. Avery (1822-1904), Robert Garrett (1847-1896), Mary Frick Garrett, later Mary Jacobs (1851-1936), Arabella Worsham, later Arabella Huntington (1852/6?-1924), Carolus-Duran (Emile-Auguste Carolus-Duran) (1838-1917), Levi Leiter (1834-1904), George Nathaniel Curzon, Marquess of Kedleston (1859-1925), Catharine Lorillard Wolfe (1828-1887), Olivia Peyton Murray Cutting (1855-1949), Daniel Huntington (1816-1906), William Bayard Cutting (1850-1912), John Worsham (1850?- 1878?), Collis Potter Huntington (1821-1900), Henry E. Huntington (1850-1927), Archer Huntington (1870-1955), Marie Louise Mackay (1843-1928), Giovanni Boldini (1842-1931), John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), Théobald Chartran (1849-1907). 4. Several of these men's collections are featured in Strahan 1879: William T. Walters, founder of the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, MD, vol. 1, pp. 81-94; William Astor, vol. 2, pp. 69-78, and William H. Vanderbilt, vol. 3, pp. 95-108. Strahan also authored a book on Vanderbilt's collection, see Strahan 1883. A work by Cabanel which Jay Gould originally purchased in 1881 from Knoedler Gallery, was auctioned from Gould's collection at Sotheby's in New York, 25 May 1994, I thank Melissa De Medeiros of Knoedler for this information. A portrait of John W. Mackay, dated 1878 and exhibited in the Salon of 1879, was auctioned at Sotheby's in New York, 23 October 1997. An engraving of Cabanel's portrait of Cyrus Hall McCormick is reproduced in Hutchinson 1935, p. 231. The original, dated 1867, is in the collection of the Wisconsin Historical Society in Madison, WI. 5. Hooper, 1879a, p. 286. 6. The name of the Viscountess of Ganay has also been spelled "Ganoy" and "Ganey" and may have been Cabanel's first portrait of an American exhibited at the Paris Salon. For commentary on the portraits, see Meynell 1886, p. 274; Mantz 1863 p. 484; and Mantz 1865, pp. 514-16. The original portrait of Emperor Napoleon III may have been destroyed or is lost. William T. Walters began negotiations to purchase a reduction of the picture in 1886, several decades after it had been painted. See Lucas 1979, p. 623. 7. Stranahan 1888, p. 399. 8. Riordan 1889, p. 78. 9. Chennevières 1882, p. 254. See also Hamerton 1901, pp. 108-9; Stranahan 1888, p. 399; Mantz 1865, pp. 514-16; Gautier 1865, p. 282. 10. See for example, Au Jour 1889, p. 2 ; Blanc 1876, p. 416; Gautier 1855, p. 248. 11. Bertrand 1870, p. 310. 12. Herton 1870, p. 2. Regarding the Birth of Venus, see for example, Cicerone 1880, p. 6. 13. Riordan 1889, p. 78. 14. Cabanel's American 1889, p. 69. 15. Johnson 1892, p. 641. 16. Wharton 1993, pp. 52, 61, 205 (page references are to the reprint edition). 17. Chennevières 1882, p. 260. 18. Origo 1970, p. 24. It is possible that some patrons had their portraits painted from photographs, even if they had journeyed across the Atlantic. Although some artists, like Léon Bonnat, are known to have used photographs to aid in painting a portrait, I have not yet come across any information that Cabanel used photographs to paint his portraits. 19. See for example, Berlin 1957, pp. 241-242, 249, 257 and Lewis 1986, pp. 79-80. 20. Luxenberg 1991, pp. 131-132. 21. Although Bonnat's first great success was a portrait of a woman, Madame Pasca, her portrait was described by some critics in masculine terms. See Luxenberg 1991, p. 144. 22. Although Cabanel painted portraits of men, in a darker and more austere palette than in his portraits of women, they excited little comment. Of the forty portraits that he exhibited in the Paris Salons during his career, only six depicted men: a government official, Rouher in 1861, Emperor Napoleon III in 1865, a public prosecutor, Delangle in 1867, John W. Mackay in 1879, the Abbot Pailleur in 1886, and an unknown man, a Mr. P, in 1887. Aside from the portraits of Napoleon III and the Abbot Pailleur, there is little commentary on the other portraits in Salon criticism. For commentary on the portrait of Mackay, see Hooper 1879c, p. 189. For commentary on the portrait of the abbot, see L.K. 1886, p. 3, Nécrologie 1889, p. 3, and Olmer 1886, p. 78. Refer to note 9 for commentary on the portrait of Napoleon III. 23. Avery 1979, Lucas 1979. 24. Lucas 1979, v. 2, p. 609. 25. Avery 1979, p. 706. Avery's entries indicate that he went to artists' studios on business: to make arrangements for commissions, to check on progress or to make payments or purchases. In this case, he probably stopped at Cabanel's studio to check on the progress of the portrait. 26. Lucas 1979, v. 2, p.620. 27. A full-length portrait of Madame van Loon was arranged in 1888 through Goupil in Paris, for 30,000 francs. See Goupil 1846-1919, vol. 12, no. 18869. 28. Lucas 1979, v. 2, pp. 473-474, 509. 29. Nonne 2003, p. 41. 30. Simon 1995, p. 139. 31. Vento 1888, 207. 32. Capital Society 1888, p. 11. Levi Leiter (1834-1904) later had Cabanel paint his portrait as well. 33. Capital Society 1888, p. 11 and Nicolson 1977, p. 27. 34. Mary Leiter and her father went to Europe in May 1888, spending ten days in Paris. It is possible that they went to the Paris Salon, which opened in May, to see her portrait in the exhibition. Nicolson 1977, pp. 32, 36. 35. Nicolson 1977, p. vii. 36. See Metropolitan 1887, p. 6, for an excerpt from her will regarding the bequest. 37. The painting is undated, and the circumstances regarding the commission of a replica of Cabanel's portrait of Wolfe by Daniel Huntington for Grace Church are unknown. 38. For basic biographical information, see National 1953, v. 38, p. 449. For a recollection of her personality and charity, see Origo 1970, pp. 25-26. Cutting was also one of Mrs. Astor's famous "Four Hundred." See Patterson 2000, p. 214. 39. Patterson 1996, p. 97; Johnston 2000, p. 22. 40. Her husband published a catalog of her collection. See Jacobs 1938. 41. There is some confusion regarding her first husband, about whom little is known. See Thorpe 1994, pp. 308-309. 42. Delaborde 1889, pp. 236, 245; Paris Salon 1883, p. 263; Stranahan, p. 399; Mantz, 1865, pp. 514-16; Gautier 1865, p. 282. 43. M. Alexandre 1889, p.124. 44. Stranahan 1888, p. 399. 45. Hooper 1879b, p. 314. 46. Charity 1887, p. 8; Strahan 1879, p. 120. See also Huntington 1887. 47. Strahan 1879, v. 1, p. 120. 48. Rowlands 1889, p. 14. 49. Wolfe Pictures 1887, p. 4. 50. Charles Frederick Worth (1825-1895), was the couturier of European aristocracy from the early 1860s on, and Americans soon followed in their footsteps. See De Marly 1990, pp. 90, 98, 168, 198, and 212-229. 51. Carter 1903, pp. 26-27; Origo 1970, p. 24. 52. Rowlands 1889, p. 14; Rabinow 1998, p. 49. 53. Vento 1888, p. 172. 54. Origo 1970, p. 26. 55. Zola 1970, p. 294. Also quoted in Simon 1995, p. 154 as "transforms women's bodies into dreams." 56. Vento 1888, p. 172. The Countess visited Cabanel in his studio while he was still working on the portrait of Cutting which was in his studio along with another nearly finished painting, his full-length portrait of Madame van Loon, which he subsequently exhibited in the Salon of 1888. Refer to note 27. 57. Origo 1970, p. 25. 58. This photograph, Z24.621 VF, is in the collection of the Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore, MD. 59. Cabanel's American 1889, p. 69. See also Vento 1888, p. 208. 60. Vento 1888, p. 209. 61. Berlin 1957, p. 388. 62. Rabinow 1998, pp. 50, 54, note 13. 63. Strahan 1879, p. 120. 64. Berlin 1957, p. 388. 65. Wolfe Pictures 1887, p. 4. 66. Nicolson 1977, p. 79; Peacock 1901, pp. 274-275. 67. Riordan 1889, p. 78. 68. Blanc 1876, p. 431. 69. Thorpe 1994, p. 307-309. 70. See Weisberg 1997, pp. xix, 77, 139, 215, 216, and 223 for examples of Chartran's work. 71. For an overview of American portraitists in the nineteenth-century up to 1870, see Gerdts 1981. 72. Strahan 1879, vol. 1, p. 120.

|